Violence takes many different forms from physical violence such as hitting to mental violence such as name-calling. Usually other people inflict violence on us but it is not unusual for people to inflict violence on themselves. What are the causes of violence? This has been written about by many people and the literature is usually very accessible. Most libraries will have several shelves of books covering the topic.

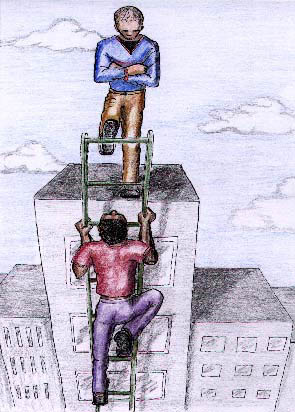

It has not often been suggested that our 'belief' system or more correctly the way in which we unconsciously order or rank concepts play a part in how we deal with or relate to violence. The following essay explores amongst other ideas, how making certain concepts more important to our life, such as those of frustration; desire and how we deal with or see other people and ourselves can influence the level of violence in society. It avoids as much as possible the use of academic jargon.

Introduction

Somebody said once that if tigers could talk, we would not be able to understand them. Their formulation of the world would be so different from our own that translation would be impossible. The potential impossibility to translate or to understand an other or even one's self has preoccupied the author for some time. This difficulty is added to when a different language and a different epistemology is brought into the frame. We all know that a joke translated from one language to another appears to lose much of its humour, even when the languages have been living next door to each other such as those in France and England. At least the people in these two countries would have had the benefit of mutual sharing of ideas and language. Within anthropology this is not often the case. It is popularly believed that anthropologists spend much of their time explaining other cultures, what they do, how they do, where they do and why they do. These questions are rarely asked of the anthropologist, especially the 'why'. Why anthropologists study other cultures rather than their own is an interesting question, a question I suspect that has a great many potential answers. All explanation has elements of translation and interpretation, even when we are explaining ourselves. How many of us have difficulty in explaining how we feel to ourselves, let alone other people? The answer is, I believe, most of us. Getting people to understand us completely is impossible, even when they belong to the same culture, but then the job surely of anthropologists is not to attempt a full understanding of a particular society, but to get some understanding. As Hobart says "there is, after all, no reason why translation should be an all-or-nothing business. Why can there not be degrees of understanding and misunderstanding?" (1982: 16).

Anthropology has its own history, and explanation has been attempted via various starting points. Tyler for example, when studying religion, used as his starting point what people believe1, Geertz a hundred years later used as his starting point how people believe2. Whatever the starting point, before we explain we need to have a degree of understanding. This I suspect is where many problems start.

1 Tyler defined religion as a 'belief in spiritual beings' (1871: 424).

2 Geertz defined religion as 'a system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive and long lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic' (1973: 90).

Anthropologists come from a particular cultural background and are immersed in their own pre-suppositions. To understand something we need, or more correctly are forced to translate it within these pre-suppositions, within a particular discourse. Whether conscious or unconscious, we have assumptions of how things are, if we look for something we have the assumption that it is there. We can see this happening from the beginning of any study. For example, in asking the question "what is the essence of ... ?", one is already assuming that it has an essence. It also begs the question "what is essence?". The concept of essence, like that of spirit or soul is hard enough to pinpoint or understand in our own culture, and yet it is one of the many concepts used by anthropologists in explaining other cultures. European and American anthropologists usually like to study people far away from their own culture, and more often than not, they study people who have no opportunity1 to study the culture of the anthropologist in return (or independently). The author is not suggesting that anthropology should become a subject of mutual-laboritization, but we must continue to recognise that much of what we have translated about other people may bear no resemblance to how the people themselves actually see things. The anthropologist may argue that the sharing of ideas does occur during the research process, but it all starts from the pre-suppositions that the anthropologist holds, whether they be conscious or unconscious.

Most anthropologists when starting out on a study will, as a matter of good working practice, read as much as they can about a people, and therefore get as much background information on them as possible before starting out on an expensive research trip. As suggested earlier the flip side to this is that it can give us a picture of a people that we go out and find, and if we go out of our way to find something then more often than not we will find it. This could mean that a series of anthropologists exploring a particular culture could come up with the same observations, thus validating each other. An observation carrying with it a very sound argument, does not mean that that observation is true, or a true representation, or indeed a good translation. It might be the case that these translations tell us more about ourselves than they do about other people.

1 The author notes that they might not have the desire to study the culture of the anthropologist.

Translation, like understanding can become particularly difficult when we are talking about things that cannot quite be grasped, such as concepts, ideas, feelings and thoughts. We all have our own understanding of what these might be, and even if we have the language to explain what these are, there is no guarantee that another person will have the same understanding. This particularly became apparent to the author 20 years ago, while he was living with the Temiars of Kelantan, Malaysia, and where he came upon the concept of selantab. 'I was 14 years old at the time, and had heard nothing of this concept before. My understanding of it then was that if one refused an offer (particularly an offer of food) then one would suffer an accident. It was quite a simple interpretation, but one I found the need to dress it up on return to England. When I returned to England, after spending 18 months with the Temiars, I was then reading everything I could about them. Anthropologists and travel-writers alike added to my raw experience. My understanding changed. No longer did I see selantab as a word similar to 'danger', but spirits and supernatural powers came into the equation'. At this point it must stress that the concept of selantab has been rarely discussed, even amongst anthropologists; where it might take up one or two pages of a thesis, but where it has been seen as a very powerful notion. Re-reading the old literature and the new, the author came across other concepts, similar to selantab, such as punan, or punen, or p'non, kempunan, or pehunan, or kapuhunan, and ke'oy. These are words used by different people across Malaysia that appear to be very similar in meaning. The word punan seems to be the most widely used and the most widely understood.

For the reader to have an understanding of the concept, a brief outline follows, but it must be stressed that the author does not intend to suggest that this is a universal concept among people in Malaysia. This explanation is also not a definition, but a generalised translation of the authors interpretation of the various concepts found.

Punan then is a word used in the context of sharing, whether it be the sharing of food, luxury items or community interaction. It is a word often used by adults to promote sharing in children, the lesson being that if one does not share with others then one will cause them pain. It could be argued that causing pain to others is like causing pain to oneself, especially in a close knit community. A person who is in pain is a vulnerable person and therefore will be liable to have some kind of accident or some kind of emotional depression. It is interesting to talk about 'cause' and 'causation', because it seems that punan is outside the cause and effect discourse, being a fusion of both cause and effect. For example, punan refers not only to the refusal of food (cause) but also to the resulting vulnerability (effect) in the person who did not get their share of the food.

With this short interpretation we can already see that to discuss such a concept within European or American discourse can lead in to all kinds of difficulty. We need to question basic assumptions. Was Lèvi-Strauss right in suggesting that structure is borne out of oppositional dichotomies? If this is the case for Europeans and Americans can we say that this is a universal world-view? Scientific theories of cause and effect might be non-sensical to some people, we can say the same of religious theories such as a belief in souls. And yet other people, it seems, are explained in relation to these concepts by European and American anthropologists.

True understanding might be impossible, but this is not going to stop anthropologists studying other people, for whatever reasons, and we can be that the reasons are many. The following chapters are not aiming for a true translation, as the author believes this impossible, but is an exploration of the concept of punan and the many theories that go with it. It will attempt to explain why some theories have taken precedence over others, and why some themes appear to have a recurring nature. The author will not be suggesting that any of the theories are wrong or even that they might be bad translations, but will offer a review of the current debate and will suggest possible alternative translations.

Chapter 1

Chapter 1

What has been written about punan?

Most anthropologists who have studied groups of people in Malaysia have come across the concept of punan. Although not always the same word is used, in all cases it seems, a person becomes vulnerable to some kind of accident when a mental or physical desire has not been satisfied1. Like concepts of 'depression' and 'stress' it is usually the victim, not the perpetrator that suffers. Ivor H. N. Evans wrote about religion and custom in Malaysia. "[There] are some very curious beliefs ... connected with food, drink or narcotics ... Misfortune will overtake anyone who goes out in to the jungle with some craving unsatisfied"(1923: 237). He goes on to say that "'jungle Malays' have translated kempunan as being "bitten by a snake, or a centipede owing to going out with a desire for food, tobacco or sireh2 unsatisfied" (1923: 237)". Although he never received an explanation as to why misfortune should follow unsatisfied craving, Evans assumed that it was due to attack from supernatural beings, or spirits. He persisted with this view even when told by some Jakun people that they did not believe spirits were connected with punan, ignoring this, he suggested that the Jakun perceive punan as a 'spirit' to be appeased with offerings. A 'headman' of the 'Behrang Senoi' might have helped him in this direction when he told Evans that "is people acknowledge a Dana Punan (Desire Spirit) who is responsible for the misfortunes met" (1923: 239). He concluded by saying that this "ll-luck occurs owing to loss of soul-substance due to unsatisfied craving ... anyone whose soul-substance is not in an active and healthy condition falls a victim to the attacks of evil spirits "(1923: 294).

Evans also drew parallels with a word used by an Ulu Kinta man (Temiars), shalantap, a word spoken when sharing out food. He suggested that through 'greediness' "if one Sakai is given something to eat, all others expect to receive a little too, even if they see that your stock of that particular article is almost exhausted " (1923: 239).

1 This desire for something could be conscious or unconscious

2 Betel-leaf

Punan seems to have been most discussed amongst the Semai. Robert Dentan suggested that the concept of punan pervades all Semai relationships. "Implicit in Semai thinking about punan is the idea that to make someone unhappy, especially by frustrating his desires, will increase the probability of his having an accident that will injure him physically."(1968: 55). He went on to suggest that punan is both a 'sanction' and a set of 'rules' that enforces proper behaviour in Semai society, and that these 'rules' are geared towards the promotion of sharing and of non-violence. "The Semai are not the sort of people who would do each other physical harm. After all, a punishment that afflicts the victim rather than the offender is unlikely to deter the latter if he is unscrupulous " (1968: 55). Dentan compiled a set of punan 'rules' relating to economic 3 exchange for the Semai. These were:

- One should not calculate the amount of a gift. "In this context saying thank you is very rude, for it suggests, first that one has calculated the amount of a gift and, second, that one did not expect the donor to be so generous. In fact, saying thank you is punan " (1968: 49). It also prohibits the direct exchange of goods.

- One should share whatever one can afford. "Not to share is punan "(1968: 49).

- One should not ask for more than a person can afford.

- "The final rule is that it is punan to refuse a request" (1968: 49).

These last two 'rules' mean that "people rarely ask for outright gifts for fear of putting the donor in punan" (1968: 49).

Unlike Evans and many other writers, Dentan does not assume the role of 'spirits' in punan sanctions for the Semai. There is also no recourse to supernatural cure. "There are two courses of action immediately open to the victim. He may simply endure the punan, or he may go to the offender and ask compensation" (1968: 56).

3 Dentan suggested that the introduction of money was devastating to the aboriginal economy. "Consequently the east Semai are beginning to exempt money from the rules governing the distribution of food": (1968: 50). Punan's locus is the heart. Punan accidents result from a victim's heart being 'unhappy', and "depression in Semai theory is life-threatening"(Dentan 1987: 627). This suggests that any action likely to make one feel hurt, will put the one that has been hurt in even more danger. These are "all actions which can kill people" (1968: 627).

Clayton Robarchek followed much of what Dentan suggests, saying that pehunan is a key cultural concept of the Semai, and is a "state of extreme danger caused by failure to have one's wants satisfied " (1986: 182). He clearly states that the 'person left unsatisfied incurs pehunan' (1986: 182). Unlike Dentan, Robarchek brings spirits back into the equation. In pehunan a person "may be attacked by a tiger, bitten by a cobra, or attacked by a 'spirit'"(1986: 182). He also suggests that one can procure charms, or involve the "securing of spells or other types of supernatural intervention to warm off the expected attack " (1977: 775).

Agreeing with Dentan, Robarchek argues that pehunan inhibits violence and aggression. He suggests that in the West, the 'normal' response to frustration is aggression, whereas with the Semai, when frustration does occur, "the resultant emotion in the frustrated party is not anger but is rather a fear of the danger to which one has become vulnerable " (1977: 769).

The Chewong also have the idea. For them, Signe Howell suggested, there are three kinds of punen. The first, like that suggested by the others is to do with avoiding unfulfilled desires and that any desire if possible must be gratified. This does not result in a glutton for desire but this rule along with other "rules are directed towards the suppression of emotionality " (1985: 5). Not to share food would be punen to those people "who are not given their share - the implication being that they would want it - and even if they did not know about the offence committed against them, they will nevertheless suffer the consequences of the act of withholding " (1985: 6). Howell does not talk of spirits but of souls, if the first rule of punen is broken, "a tiger, scorpion, millipede, or snake will bite. No differentiation is made between the bite of an actual animal or of its 'soul' (ruway)" (1985: 6). It may appear as an actual bite or as some kind of illness. The second type of punen means that pleasurable events must not be anticipated verbally, and the third type keeps people from showing emotion in the face of accidents. In the last two cases Howell suggested that the consequences of these are the same as the first type of punen, but the 'causes' are different. "In these cases only the actual physical tiger attacks, not its ruway " (1985: 7). Punen as with all of the above accounts is to do with satisfying desire, or suppressing it. The victim suffers. Unlike Dentan's picture of the Semai, where the heart is suggested as becoming unhappy, Howell suggested that for the Chewong, the liver (rus) is the seat of all thought and feeling. There is no dichotomy, thoughts are feelings and feelings are thoughts. This is the same for punen; by saying punen, one is not only referring to a particular rule that has been broken, one is also "giving a diagnosis" (1985: 11).

Evans earlier introduced us to the concept of shalantap, paralleling this to punan. Geoffrey Benjamin suggested that "one of the cardinal principles of Temiar society - [is that] if one is requested to give something to someone else then he must give ... failure to give when requested involves sanctions of the sort best described as 'supernatural'. In this particular case the sanction involved is that of selantab " (1967: 336). He goes on to say that the Temiars place more stress on sharing one's possessions than of satisfying one's desires. Benjamin selects two areas of importance within the concept of selantab. Firstly, one must accept what is offered whether or not one wants to [and] secondly, the sanctions that follow a breach of [this] proper behaviour fall not on the one who fails to give, but on the one who fails to receive" (1967: 337). He also quotes Geddes, writing about the Land Dyaks related principle of panun, which "makes it clear that a system of sanctions so markedly other-directed can serve admirably as a means of infusing the whole community with a moral concern for one's fellows" (1967: 337). Selantab, Benjamin suggested, is one of many sanctions of social control among the Temiars where the victim suffers. Such as serenlok, where a person who has been made a vain promise could meet with misfortune.

Sue Jennings suggested that "selantab is a form of ritual generosity"(1995: 54). Visitors to Temiar houses will always be offered food and tobacco. "If food is not readily available, a child is sent quickly to another house to obtain cassava or rice that is then cooked and proffered" (1995: 54). If at least a token has not been accepted then the visitor will suffer an accident "or get bitten by snakes or other creatures" (1995: 54). Like Benjamin, Jennings stresses the importance of sharing in Temiars life, "if someone is asked for something, there is an expectation that it will be given, otherwise misfortune, such as a fall or a bite, will come on the person who asked in the first place" (1995: 54), this is apparent even in children. There is an obligation to give and an obligation to receive and "neglect of these constraints can be dangerous, resulting in major illness or death" (1995: 43). Neither Benjamin or Jennings talk about there being a 'cure' for selantab. One either endures it or preferably one does not put oneself in the position in the first place. Marina Roseman, who also studied the Temiars, agrees with those quoted above that it is similar to the Malay kempunan, that if someone refuses a request or refuses to receive will be in a 'state' of vulnerability in which one is "likely to be bitten by a snake, a scorpion, various stinging insects, tigers, or to wound himself" (1982: 8). She suggested 'longing' and 'desire' in the Temiars is not escaped with 'quick-fixes', rather "they create a ceremony in which they can bring the spirits back to them through song and dance, momentarily fulfilling otherwise inchoate longings" (1993: 158-9). For Roseman, selantab can also be cured or mediated by certain humans (shaman). Naming these 'illnesses' (perenhood, serenlok and selantab), does not attract them back into Temiar domain, "rather it startles the illness into departing" (1993:29).

Roseman's account is very similar to both Jennings and Benjamin. Apart from there being the possibility of 'cure'. The previous writers have all talked about rules or sanctions, Roseman is no different, and she similarly points out that "Temiars do not conduct their lives rigidly rule-bound ... cultural rules are always being tested, played with, and chanced" (1993: 146). Within this we are told that "the patient [has a} responsibility misfortune" (1993: 146) incurred. She also suggests that the rewaay (head soul) is vital in Temiar life, but this is not where ones thoughts are. In fact like previous writers she tells us that there is no dichotomy between thought and feeling, but unlike the Chewong locating these in the 'liver', for the Temiars "the human heart soul is the locus of thought, feeling and awareness" (1993: 31). Roseman suggests that the dichotomy is rather between inner experience and vocalised expression, she Quotes one of Benjamin's informants in support of this; "The heart soul controls our thoughts while the head soul enables their utterance" (1993: 32).

Kirk Endicott found a similar concept with the Batek, called ke'oy. Although this disease, as Endicott calls it, does not explicitly surround the concept of food, it is a serious condition caused by one being frustrated in some strong desire, or who has had a fright, or who has been mistreated by other people in some way. It is an "affliction of the heart ... an emotional depression usually accompanied by physical symptoms such as fever. This is regarded as a serious disease which can lead to death" (1979: 109). Endicott suggested that the Batek can treat this disease with either 'spells' or 'cause-removal'; "spells and lime paste are supposed to drive the disease out of the heart" (1979: 109), or a cure can be effected by removing the cause of the disease, for example "an alleged offender ceases to be angry with the victim" (1979: 109). He goes on to say "the idea that one can cause a person to become ill and die by mistreating him helps to ensure that the Batek treat each other fairly" (1979: 110). Endicott tells us that ke'oy is a 'social' disease, caused by people, and has nothing to do with the impersonal forces of nature.

Evans suggested that the concept of punan in found in both Malaysia and Indonesia. The examples so far have been from Malaysia. In Indonesia, Anna L Tsing studied a group of people called The Meratus, of South Kalimantan. She found there the concept of kapuhun, which she suggested was to do with isolating oneself off from other people or from one's environment. "One can mangapuhun another person by withholding something he or she requests, and one can be kapuhunan oneself by refusing offered food ... one becomes vulnerable to accidents, such as bites by poisonous snakes or centipedes, as well as to illness" (1993: 189). Tsing suggests that there is a cure for kapuhun which she describes as a "disease splinter", it can be sucked out or dissolved by a shaman. This is similar to Evans who says that "Punan stabs those who have offended" (1923: 238). The difference being that in Evans view punan is some kind of 'god' inflicting punishment, whereas Tsing would say that punan is a disease where the "offending agent may be something in the forest, or it may be something much closer to home - domestic animals, children, even hearth stones can mangapuhun [a person]" (1993: 189).

Wazir-Jahan B Karim studied the Ma'Betisek. Karim suggested that we can understand the Ma'Betisek 'belief system' through the exploration of two opposed concepts, that of tulah and kemali. "The word tulah literally means 'curse'. It expresses the idea that plants and animals have been cursed by the forefathers of the Ma'Betisek to become food for humans" (1981: 1). Karim believes that this is their justification for being able to eat animals and plants. In opposition to tulah we have kemali which "expresses the idea that acts involving the killing and destruction of plants and animals bring humans misfortunes and death because both plant and animal life are derived from, and are essentially similar to, human life" (1981: 1). In the context of kemali, plants and animals will "attack and kill them (people) if humans experience certain states of deprivation known as punan" (my brackets 1981: 10). Karim suggested that the Ma'Betisek defined punan very similarly to the Semai, she gave us the following deprived 'states' where people could find themselves in punan: "the inability to eat a desired food, to see or meet a loved one, to have a child, to attend an important ceremony held by a close kinship or rejection from kinsman, parent or child" (1981: 10). Karim tells us that Tulah is associated with the 'transgressions of the moral order' and that kemali is associated with the 'breach of certain taboos' (1981: 32/43). Rosemary Gianno studied the Semelai. She found that they observed a lot of prohibitions so as to steer clear of suffering from misfortune. The first one she describes is the concept of ma' pnon, which she suggested is similar to kempunan. Gianno tells us that two kinds of action can precipitate ma' pnon. Firstly "is the neglect of the rule that any food that is witnessed being eaten or is in the process of being prepared for eating, should be shared by the witness, if not in full, then at least ritually ... Failure to perform this act leaves one open to a subsequent mishap ... The second type of action that can precipitate this condition is to say the real name of a variety of foods while in vulnerable circumstances, i.e., in the wild" (1985: 108). According to Gianno, some states of misfortune can be cured by most Semelai adults who know the right "incantation or spell" (1981: 112), but for the more serious cases help would have to be got from a shaman.

MOHD Taib bin Osman studied Malay 'folk beliefs', he suggested that all diseases are thought to have been caused by 'noxious spirits' in people's bodies. These, he says, can be cured by shamans. More specifically, these spirits can damage a person if their semangat is weakened in any way. Semangat, Osman suggested can be translated as either ""Soul", "Spirit", "vital force", "life force", and "Mana" ... each man and each object is the "house" or "sheath" of his or its own semangat" (1967: 122-3). Osman suggested that kempunan is associated with semangat. If people are suffering from lack of, or damaged semangat, they will be open to kempunan. "It is believed that a person will meet a mishap if his craving for a certain food is not satisfied. It is said that the ill-luck occurs because the semangat of the person is lacking in strength due to the unsatisfied craving" (1967: 124).

Chapter 2

Interpretation of interpretations

With all but one of the interpretations in the previous chapter we can see a broad degree of consensus, particularly in the area of sharing and the fulfilment of desire. Benjamin suggested that more emphasis is placed upon sharing than of satisfying desire, but this could be just another way of looking at it? It is possible to say that through sharing, desire is satisfied. Selantab does not only apply to food but also to "clothing and luxury goods"(Benjamin 1967: 337). In the same vein it is interesting to note that ke'oy is not associated with food, in fact the Batek, Endicott suggested, "consider the necessity of eating to be a nuisance" (1979: 89). If eating is a nuisance, then one is not likely to be frustrated by it, hunger in this case ceases to be a desire that must be satisfied, rather a burden one endures. Evans on the other hand interprets in opposition to the concept of sharing, suggesting that we are witnessing the satisfaction of greediness. Where disagreement (if I can call it that) occurs is in the search of cause and effect, and potential cure. We have a fusion of cause and effect, we have the involvement of supernatural agency including "the bites and stings of centipedes, scorpions or snakes; the cuts of sharp edged plants; or the breaking of a limb through falling over stumps or from the misdirected felling of a tree" (Benjamin 1967: 336). Some authors suggest cures through spells and/or shaman, others suggest endurance, or the seeking of compensation for punan. Most authors tacitly if not explicitly suggest that the lives of the above mentioned people revolve around religious observance and ritual practice. 'Every aspect of repeated everyday behaviour has for the Temiar an associated value deriving from its categorization within the totemo-ritual-cosmological system' (Benjamin 1967: 20). If this is the case then it is not surprising that in these texts we find the 'supernatural' pervading all aspects of Temiars life. In the authors opinion, some Temiars might see it this way, but the author would dare to suggest that the supernatural and/or the religious does not pervade all areas of Temiar life, and that some Temiars, just as other people, may have no sense of the religious at all. The 'Jakun' who told Evans in 1923 that 'evil spirits' were not connected with punan may well have been right.

When supernatural agency is suggested for 'punan sanctions' , it is usually in the form of the 'spirits' or 'souls' of other entities that attack or invade the victim or the 'soul' of the victim. Llyn De Danaan studied Malay healing arts and suggested that Osman was linking "semangat with desire" (1984: 152), De Danaan quoted Osman when linking this to kempunan. Although there is no other mention of kempunan, De Danaan does talk about desire. "Desire, it was explained to me, comes from the senses" (1984: 156), such as sight, hearing, touch and so on. In this context "a rebab player ... is often blind, i.e., without desire" (1984: 156). De Danaan was suggesting that if we can lose our senses we can lose our desire and therefore we would cease to put ourselves in any danger of misfortune. Without any sense I do not suppose we would care one way or another! Like Osman, De Danaan tells us that kempunan can be cured. In this case, one of unrestrained desire, the rebab player can help effect a cure, or to "correct the results of desire in humankind which can be manifest as jealousy, envy, unfaithfulness as well as withdrawal, headaches and stomachaches" (1984: 156).

Chapter 3

Spirits and souls

In the context of punan, the concepts of spirit and soul or soul-substance play a very important part in most explanations. This initially raises the problem of the pre-supposition of dichotomies. In English analyses spirit and soul have been regarded as different, Evans-Pritchard suggests that they are not only different but 'opposed, spirit being regarded as incorporeal, extraneous to man' (1965: 26). More recent studies suggest that spirit and soul are the same thing in different situations. Benjamin, drawing on Endicott suggests that 'spirit equals the free soul and soul equals the bounded spirit' (1974: 10). This compliments Osman who translated the Malaysian term semangat as 'either "Soul", "Spirit", "vital force", "life force", and "Mana"' and went on to say that 'each man and each object is the "house" or "sheath" of his or its own semangat ' (1967: 122-3).

Although we have now broken down the dichotomy of spirit/soul, we are nowhere closer to finding out what it is, if indeed it is something at all. If we do not know what it is, will it help us to suggest what it is not? Although spirit/soul has been described as a substance (eg Endicott), it appears as though we cannot see it, touch it, smell it, hear it or even taste it. It has not been described as having any particular shape, nor being any particular size, we are not told what colour it is or how much of it there is. We could go on like this forever, still we are no closer. Delving deeper into what people have said it is, we can say that spirit/soul can be different strengths at different times, all entities have at least one, the loss of or the weakening of spirit/soul can lead to death, spirit/souls can travel/leave the body/house, the entering of a foreign spirit/soul to ones body/house can be dangerous, spirit/souls can be manipulated by trained practitioners, spirit/souls can act on their own, spirit/souls have an effect on their bodies. Spirit/soul is being described as something fundamental to all living entities, damage of which can lead to vulnerability, but reachable only through the cooperation of specialists (eg shamen).

Essentially, spirit/soul is what makes us what we are. We might even go as far to suggest that it is what we are, that it is in fact our identity, or at least makes up part of our identity. As Howell suggests amongst the Chewong who told her that in some circumstances, when the soul of something bites another, no differentiation is made between the bite of the actual thing or the bite of its soul (1985: 6). The author stresses that 'identity' is not necessarily an improvement on the translations offered, but it does allow us to move outside the concept of religion.

One of the earliest writers to discuss punan, Evans, assumed that 'spirits or supernatural beings' were involved in attacking humans, who contravened punan rules, a view he continued to suggest after hearing from the people he was studying that this was not the case (1923: 239). Many of the anthropologists who followed Evans in Malaysia agreed with his suggestions, with a few exceptions. The first, most notably, is Dentan, did not assume the role of spirits or supernatural beings, but suggests the concept of 'depression' (1987: 627). Similarly, Endicott steers clear of the supernatural and talks of a 'social disease', caused by people, [that] has nothing to do with the impersonal forces of nature (1979: 110). Ones identity is socially constructed, it can be argued that loss of one's identity can lead to depression. Depression is a social disease.

Although many anthropologists assume spirit belief to be prevalent amongst most (all) indigenous people's around the world, such talk of spirits can lead to exoticisation and potential misrepresentation of the people concerned. For example, the Temiars word rewaay is translated as 'head soul', the author suspects could equally be translated as 'identity'. He is not suggesting which is the best translation, rather he is suggesting that indigenous people's lives are not totally structured around the supernatural, and that concepts such as spirit, soul and identity can lose a lot in translation, and may ultimately in fact mean something totally different. This is emphasised by Needham when he suggests that the notion of 'soul-substance' could be incorrect and that 'it emphasises the crucial importance of the interpretation that the ethnographer gives to the evidence' (1976: 75/6). We must remember that people immersed in the same culture will often interpret in different ways, just as anthropologists do, concepts are not concrete categories in any language, but malleable in many directions.

Chapter 5

Cause and effect

A notable feature of punan is its apparent fusion of cause and effect. Dentan suggests that punan is both a sanction and a set of rules (1968: 55). Howell also explicitly states that there is no dichotomy, and goes on to say that by saying punen one is not only referring to a particular rule that has been broken, one is also 'giving a diagnosis' (1985: 5). This presents us with difficulties. The dichotomy between spirit/soul was difficult to overcome, the cause/effect dichotomy is so central to western theories of knowledge that without it we can lose meaning. As Levi Bruhl suggests; 'our own ideas of causality are so specific to a western theory of knowledge, as elaborated from Plato and Aristotle down to Hume and Kant, that when analysing alien traditions of thought we should find [alternative] terms ... [but] there is no way of doing this ... we still have to use the word "cause"' (quoted in Needham 1976: 80). Needham in his discussion of head-hunting and soul-substance makes the point that 'ethnographers, failing to elicit an idea answering to their own expectations, postulate an abstraction (a mystical kind of force) that satisfies what for them is a necessary condition of the relation between cause and effect' (1976: 84). It is not surprising, in the light of the above, that ethnographers such as Evans looked for, and found causal spiritual agents in the context of punan. In Evans words, 'ill-luck occurs owing to loss of soul-substance due to unsatisfied craving ... anyone whose soul-substance is not in an active and healthy condition falls a victim to the attack of evil spirits' (1923: 294). Osman, over 40 years later states that 'ill-luck occurs [due to evil spirit attack] because the semangat of the person is lacking in strength due to unsatisfied craving' (1967: 124).

Both of the above accounts are almost identical except that Evans was talking about Temiars and Semai, and Osman was talking about folk Malay beliefs. The author suggests that what we see in the above accounts is the attribution of cause to souls/spirits:

Unsatisfied craving -(loss of soul-substance) - (attack by evil spirits) - Illness

Unsatisfied craving causes loss of soul substance which causes evil spirits to attack which causes illness. It was not enough for Evans to say that illness results from unsatisfied craving, as he has been told by the people he was studying. Taking out the spirit/soul dichotomy still leaves us with a dichotomy of cause and effect, whereas punan suggests a fusion:

Punan - Punan

Unsatisfied craving - Illness

We could tentatively suggest at this juncture that unsatisfied craving = illness, which would present us with a new cause and effect dichotomy:

Punan - Punan

Broken rules - Illness

This could bring us full circle if we therefore assume that broken rules = illness, and that illness = broken rules. Howell can help us at this point, when she suggests that for the Chewong there is no dichotomy between thought and feeling, thoughts are feelings and feelings are thoughts. Roseman goes further when she suggests that for the Temiars, thought, feeling and awareness are all located in the same place (heart) and that the dichotomy is rather between inner experience and vocalised expression. Which could give us the following:

Punan - Punan

Broken rules (thoughts) - Illness (feelings)

Or:

Punan - Punan vocalised

Inner experience (broken rules & illness) - Vocalised expression (ill due to broken rules)

Thoughts, feelings, emotions awareness and experience are located together, the separation comes about when these are expressed vocally to others or expressed to oneself.

Let us now apply this to an actual punan occurrence to see if, in Hobart's words we can get a degree of understanding:

A man wants a cigarette, he asks his friend for one, he is refused, he goes to work, he thinks about the cigarette that he did not get, he bumps his head, his head is hurt/bruised, he tells the story in retrospect (A Kensiu story supplied by S. Nagata - personal communication 1997).

- A man wants a cigarette (thought, feeling, emotion - desire - potential punan)

- He asks for a cigarette (thought, feeling, emotion into public arena - desire expressed)

- He is refused (thought, feeling, emotion publicly unfulfilled)

- He goes to work (thought, feeling, emotion ignored - punan endured)

- He thinks about the cigarette (thought, feeling, emotion intensified)

- He bumps his head (thought, feeling, emotion damaged - punan invoked)

- His head is bruised (thought, feeling, emotion publicly damaged)

- He tells the story (reason for damaged thought, feeling, emotion publicly vocalised)

Desire - desire vocalised - desire unfullfilled - unfullfilled desire ignored - unfullfilled desire intensified - illness - evidence - reason

Although we have now deconstructed the dichotomy between thought/feeling, we still have the dichotomy of cause/effect:

Punan - Punan

Unfullfilled desire - Illness

To deconstruct further we can say that unfulfilled desire = depression, and that depression is an illness. Thus we have:

Potencial punan - Punan

Experience/expression of thought/feeling - Unfulfilled desire/loss of identity/depression/illness

Although we still have a cause, it is not a cause understandable in the western sense of a causative force, such that Needham discusses, and who suggests that it is a problem we have due to 'our preoccupation with the methods of science ... [that] can mislead us in the analysis of social facts' (1976: 84). The above conceptualisation is not professing to be an accurate translation or even a good translation and it is a far cry from the attack of evil spirits. It might suggest that all people have the potential to similar inner experience, but which or how much of these are valued, endorsed or separated out by cultural constraints is difficult to ascertain.

Chapter 6

Self and Other

Earlier we discussed the notion identity, and suggested that this could be used in place of the soul/spirit dichotomy. For this to make more sense we need to exploring relation to the dichotomy of self/other. Amongst the Temiars, anthropologists have suggested that living entities have at least two souls. 'In human beings these souls are the hup 'heart' soul and the rewaay 'head soul' - respectively the seats of doing (or willing) and of experiencing (or undergoing) ' (Benjamin 1993: 7). For Benjamin the hup is the heart and blood soul, the locus of doing, will, agency and memory. The rewaay on the other hand is the head soul and is the locus of 'undergone experience' (1993: 7/8). For Jennings the rewaay 'is clearly 'Self'-like ... the marker of bodily integrity. But it is cast in the role of a patient-like, non-controlling experiencer of whatever befalls the individual in dreams, trance and sickness' ... and it is unformed at birth, [the hup] is essential for life; it is where a person's feelings are created ... the hup represents the functions of the heart, liver and lungs in terms of a living breathing person (1995: 61& 116). For Roseman the rewaay 'is the vital, animating principal, ... language, speech and expression are functions of the head, [while the hup] 'is the locus of thought, feeling and awareness' (1991: 21/30). They are all in agreement that the 'head soul can wander off or be startled [into leaving] ... The hup does not leave the body but is subject to invasion from outside' (Jennings 1995: 76). This gives us the following picture:

Rewaay

- Located in/on the head

- Seat of undergone experience

- Self - like

- Seat of expression

- Marks integrity of the body

- Patient - like

- Non - controlling experiencer of dreams, trance and sickness

- Vital animating principal

- Unformed at birth

- Can leave the body

Hup

- Located in the heart

- Seat of the will

- Seat of doing/creation

- Seat of agency

- Seat of memory

- Seat of feeling

- Seat of thought

- Seat of awareness

- Essential for life

- A metaphor of a living breathing person

- Cannot leave the body

From this picture we can see that both the hup and the rewaay are essential for a human existence and have links with each other. The hup provides thoughts and feelings which are expressed, or vocalised through the rewaay. The previous chapter left us with the following dichotomy:

Potential punan - Punan

Experience/expression of thought/feeling - Unfulfilled desire/loss of identity/depression/illness

Which in light of the above could also be expressed as:

Potential punan - Punan

Expression of thoughts/feelings - Punan

Vocalisation of hup - Punan

Rewaay - Hup

Hup - Rewaay

There is a dialectic between hup and rewaay. It might also be possible to suggest that Hup = identity and Rewaay = expression and experiencer of identity. In any case, it seems that both hup and rewaay are components of the self, and one could suggest, both contribute in making up one's identity. It has been suggested that individuals develop their sense of identity through interaction and experiencing 'others'. 'In the process the child gradually becomes a social being in his own experience, and he acts towards himself in a manner analogous to that in which he acts towards others' (Wilshire quoting Mead 1982: 116). It could also be argued that within this process in developing identity the self can become 'other' and the 'other' can become self. 'The Temiars [have] developed a middle voice, in which subject and object become one, because the 'individual's empirical self or felt subjectivity is thus portraying as a dialectical composite of self and other' (Jennings quoting Benjamin 1995: 115). It is possible to perceive one's beating heart as 'other' or one's travelling rewaay as 'other', Benjamin suggests that one's children can also be perceived as self (1993: 1). It would be now difficult to talk of this dichotomy as being in opposition, 'self/other' is a dialectical relationship of complementarity. This would move away from a universalising notion of self /other found in many anthropological writings such as is found in the writings of Mead (1934) and Hallowell (1971) 'where the ability to distinguish self from other (self-identity) and the apprehension of self-continuity are thought to be essential for basic human and cultural functioning. In short, they are considered as universal attributes of the self' (Moore 1994: 30). Moore goes on to say that these universal attributes 'do not imply anything about the local views of the self which will be prevalent in any particular culture' (1994: 30). When we talk about the hup or the rewaay contributing to the identity, we are moving away from talking about the body, or one's body, and of other bodies. Instead we are seeing an identity made up of an interior and exterior self and an interior and exterior other. As Benjamin suggested earlier, not only could one's children be regarded as self, but also other people one interacts with could be regarded as self. It could also be suggested that this is not just limited to people, one's self and ultimately one's identity could also be made up from and are indeed part of one's interactions with animals, trees and other entities.

It would be safe to say that the self depends upon the other for validation or recognition of one's identity, I suggest that for the Temiars, unlike many Europeans, the other is more closely connected to the self, and is not always seen as a clear cut oppositional dichotomy.

Conclusion

The author would now like to go back to the beginning of this essay where it was suggested that the concept of punan could equate to the concept of 'danger'. 'If we walk on an unstabilized cliff edge there is a danger of our falling off. But falling off is itself the danger that we must be aware of. Danger means both that which constitutes the harm (the Fall), and the risk that harm will occur' (Apter 1992: 23). The same could be said of punan. For example; if D were to ask Z for all of their rice harvest, Z would most probably refuse, thus leaving D punan (in danger). It was punan (dangerous) for D to ask (particularly for so much), a refusal should have been expected, and now D is punan (in danger). If this formulation is correct, we can see why such a wide variation of interpretation is possible. Danger can mean different things to different people. It can mean ghosts, evil spirits, or even a dual carriageway, it would depend on who one asked and when. In this context, punan could be said to be both the risk and the fall itself. By saying "Danger!" (punan) one is not only referring to the trauma of falling, one is also referring to the potentiality of falling.

Mauss suggested that most 'westerners' were moral people with a sense 'of being conscious, independent, autonomous, free and responsible [whereas] the primitive ... accepts rules of behaviour as valid without question' (Ourousoff quoting Mauss 1993: 285). Most of the anthropologists quoted in this paper would not follow this line of thought, but punan has been referred to by many of the authors (see chapter 2) as part of a set of rules. The same authors would suggest that 'the people in these societies do not lead their lives rigidly rule-bound. One could not really say that 'danger' is a rule, it is generally used as a warning to protect people from harm, and unless a particular danger has been enmeshed in law, it is generally up to the individual to decide on a course for action. The same could be said of punan, people generally have a responsibility for punan incurred. The author suggests that punan cannot be a taboo either. Steiner suggests that taboo has to do with 'specific and restrictive behaviour in dangerous situations' (1956: 20), and 'a taboo clearly differentiates between those who must practice it and those that need not' (Lambek 1992: 249). The possibility for punan is with everyone, no matter whether one is young or old, man or woman, pregnant or not, and friend or foe. Some situations are more punan than others, and some people are able to cope with different degrees of punan.

If punan is not a rule, or a taboo, by extension it would be difficult to say that it is part of a moral code. 'An action is moral if and only if it is aimed at a social or impersonal, rather than individual or personal, end ' (Evens quoting Lukes 1982: 207). Punan affects the individual, which by extension affects the community. Punan therefore is not directly concerned with morality, just as 'danger' is not directly concerned with morality. Indirectly it could affect much of what we do and why. Rules like morality do not govern routine behaviour 'because practice itself is what socialises individuals ... It is impossible to know from the invocation of a rule whether the speaker has been motivated by it, or has accepted it retrospectively as part of his rhetoric of self justification' (Greenhouse 1982: 60 - 61). A person may say that something is punan (dangerous) and go and do it anyway, or they may not do it because it was punan (dangerous).

This paper has been concerned to draw the readers attention to the potential misunderstanding of other people's concepts and to therefore offer translations that might not be wholly accurate. As we have seen through the exploration in the previous chapters, it is possible to give meaningful translations of others that could mean something different to that 'other'. We get a degree of understanding in any of the translations, truer translations might come from the people themselves, if they wanted to give them, or if they were able to give them. For now we left with the anthropologists authorizing the people they are talking about; the anthropologists and the readers of their texts will get the understanding they are able to find or that they want to find.

Throughout this paper, the author has been at pains to show alternative interpretations, and also to show how some of these have been built up on Western pre-suppositions and the preferences of anthropologists. Even though the author has experienced punan (selantab) at first hand (see appendix 1) he has no idea whether or not the impersonal forces of nature are at work within punan, and if there are any cures. Sharing and non-violence certainly appears to be more important to most Temiars than most Europeans but whether punan orders this non-violence, and sharing would be impossible to say. The concept of punan certainly seems to 'promote' sharing and the considerate treatment of others, but that is as far as this author will go.

Punan also appears to promote the considerate treatment of oneself, this is particularly clear when the other can be incorporated into the self, as we have seen can happen with the Temiars. By extension it could be argued that looking after others is like looking after oneself. As we can see some degree of fusion between self and other we can see the same with cause and effect. Punan is either both, or is outside the cause and effect dichotomy altogether, as the concept of 'danger'.

Those anthropologists who did not connect punan with the supernatural talked of accidents, disease and depression. If one does not get what one wants, or is hurt by people in one's community, people will suffer with punan. It is always stressed that the victim suffers the punan. This kind of reasoning could be said of most people, including European and American. It might just be put differently; an English person who does not get what they want or is emotionally hurt by a friend or family member, will often have some degree of depression until the matter is resolved. The same could be said of accidents; if someone is feeling 'low' for a particular reason (eg hunger), they are often thought to be susceptible to accidents. Punan is also suggested as being life threatening; some people, even though all their bodily wants are satisfied, are so depressed that they commit suicide. Sweden is said to have one of the highest suicide rates in the world.

Some people take concepts like depression more seriously than others. English people tend to take depression less seriously than other physical illnesses. It could be argued that Temiars generally take depression as seriously as other physical illnesses, if not more so. We are nowhere nearing finding the reason for depression than we are of finding a reason for punan. Maybe in our search to find reasons or causes we attribute to forces of our own making. Whether it is the weak soul of a person that makes a person vulnerable or the dented identity of a person that makes a person vulnerable is a question for the philosophers. This author is sure that their are many Temiars and Semai alike that would only be too happy to philosophise on the subject, if they thought it was worth philosophising about.

One of the difficulties that anthropologists face is that by translating 'other' discourse into European and American categories does not help in understanding the 'other', unless we can be fairly sure that their categories fit in with our own. This might be possible with 'things we can touch with our senses', but with concepts, ideas, souls and spirits must be almost impossible. We can rarely agree on such concepts in our own society, and yet we play our academic games on guessing the epistemologies of other people. There are few anthropologists who have fitted European and American categories into 'the other's' categories. One such exception is David Parkin who explored English notions of violence 'through examining the ethnography of an African society' (1986: 204).

Anthropology keeps coming back to ourselves, it might be helpful for training in 'self-analysis' to be part of the anthropologists requirements when studying others. Temiars, it seems, incorporate 'other' into 'self' quite successfully, does this help them in understanding others? Learning about the 'other' could be part and parcel of understanding ourselves and our own society. Some would say that European and American philosophy has forever drawn on ideas from other people. Indeed it was Said who said that 'the Orient has helped to define Europe (or the West) as its contrasting image, idea, personality, experience ... The Orient is an integral part of the European material civilization and culture' (1995: 1 - 2).

It is difficult for the anthropologist to know whether they are imposing themselves on a group of people, who often have not been consulted as to the proposed study. It might bring some anthropologists down to earth if again, as part of their training, they studied a group of people in their own society before attempting to study others. Jean La Fontaine and her studies of child sexual abuse and Dorothy Willner with her studies of incest are two exceptions (La Fontaine 1988: 2).

The author wanted to end this paper with a wide range of ethnographic stories concerning punan. Unfortunately, actual cases were rarely reported by anthropologists, what was written down was usually just the interpretation of the anthropologist. The author has compiled these with the examples of punan that were sent by anthropologists who responded to his request for stories, they can be found in the appendix along with the authors own examples.

Appendix Ethnographic examples of punan. S Nagata found an example of punan when he was living with the Kensiu. "A Jahai Tehedeh in the settlement I lived, pointed to a lump on his forehead and said that it had happened when he kept thinking of a cigarette that he had asked of his friend and had been refused ... [later] while working in the forest, he suddenly bumped into a tree branch" (personal communication 1997).

Evans gave this example for selantab. "One Sakai man to whom I had been talking to about these matters, having been given a couple of biscuits shortly afterwards, went around his companions, who were squatting near my tent, and chiefly, I think, with a view to giving me a practical illustration of how the customs were carried out, broke off a bit of biscuit for each man, saying as he gave it to him, "Shalantap!" " (1923: 239).

Jennings gives the following selantab example. If one for some reason "could not accept the food or tobacco [offered], then we had to take a small piece of it and rub it on our calves saying 'soh, soh, selantab ' ... otherwise we might have an accident" (1995: 54).

Robarchek gives several examples for the Semai. The first one concerns the highly prized durian fruit. "The durian season is awaited with eager anticipation. The months when there are no durian do not, however, cause the Semai to be in a state of pehunan ... However, when the season begins and the ripe fruit first falls from the trees, the danger of pehunan is intense" (1988: 767). The second is in regard to small birds that are highly desirable food. When these birds are caught "the danger of pehunan is great. One of my neighbours, in fact, referred to these birds as "ca'naa' pehunan" (pehunan food)" (1988: 768). The third example was in regard to his wife. "My wife mentioned to the headman's wife that she wanted a pair of the gold wire earrings that were popular with the village women. Some time later, after she had purchased the earrings, the headman remarked to me that it was good that I had allowed her to buy them since to have refused would have placed her in pehunan" (1988: 768). The fourth example has to do with verbalizing a want and thus making the want more explicit and thus more dangerous. "I encountered a villager one morning at the beginning of the durian season on his way down the mountain to sell three of the fruit to a trader. By way of casual conversation, I remarked "I see your durian are falling (ripe)." In response, he insisted that we open the fruit and eat it on the spot and no amount of protest on my part could shake his insistence. My having taken explicit notice of the fruit was tantamount to a request for it, and it was necessary for him to fulfil my want if I were to avoid the possibility of pehunan" (1988: 768/9).

Howell gives an example amongst the Chewong of a "woman who had died of punen radio, her husband having refused to sell sufficient rattan to provide her with one" (1985: 6).

I experienced selantab with the Temiars both in the 1970's and the 1990's. In 1995 I was helping a friend clear a field out of the forest. During the course of the day I was called down to the house for lunch, I did not immediately go and eat but said I would be along in a minute. 10 seconds later I slipped and fell on a sharp stump of bamboo and cut open my hand. I returned to back to the house and was told that because I had refused to come for lunch it was selantab. In other words both the act of refusing and the resultant cut was selantab. On another occasion, in the early 1970's, a 'headman' of a village suffered a broken leg after we had refused him more gifts that he had asked for, as we had run out of goods. At this point he asked us to leave his village. On returning to our own village we were told that the next day he had broken his leg and that it was selantab. He had asked us for something and we had refused, it did not matter that we had nothing left to give. On another occasion in 1995 I was about to follow some other people down to the river to wash, I slipped on the step of the house but was caught by a friend who muttered "selantab " to me. He brought me back in the house and said that I should eat before I went down to the river.

Bibliography

Apter, M. J. - 1992. The Dangerous Edge. New York: Free Press.

Asad, T. - 1986 The Concept of Cultural Translation in British Social Anthroplogy. In Writing Culture: the poetics and politics of ethnography. eds. J. Clifford and G. Marcus. London: Academic Press.

Benjamin, G. - 1993 Danger and Dialectic in Temiar Childhood. Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore.

Benjamin, G. - 1990 Notes on the Deep Sociology of Religion. Originally published in 1987 as Department of Sociology working paper no. 85, National University of Singapore.

Benjamin, G. - 1989 Achievemnts and Gaps in Orang Asli Research. In Akademika No. 35.

Benjamin, G. - 1974 Indiginous Religious Systems of the Malay Peninsula. In The Imagination of Reality. eds. A, L, Becker and A, A, Yengoyan. New Jersey: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Benjamin, G. - 1967 Temiar Religion. PhD Thesis. Cambridge: Kings College.

Bell, D. , Caplan, P. and Karim, W, J. (eds) - 1993 Gendered Fields - women, men and ethnography. London: Rouledge.

Burke, K. - 1969 A Grammar of Motives. Berkeley: California University Press.

Chitakasem, M and Turton, A. (eds) - 1991 Thai Constructions of Knowledge. London: School of Oriental and African Studies.

Douglas, M. - 1966 Purity and Danger. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Endicott, K. - 1979 Batek Negrito Religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Evans, I, H, N. - 1923 Studies in Religion, Folk-Lore, and Custom in British North Borneo and the Malay Peninsula. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Evans- Pritchard, E. E. - 1965. Theories of Primitive Religion. London: Oxford University Press.

Evans- Pritchard, E, E. - 1937 Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Evens, T. M . S. - 1982. Two Concepts of 'Society as a Moral System': Evans- Pritchard's Heterodoxy. In Man Vol. 17. No. 2.

De Danaan, L. - 1984 Performance and Transformation: Mystery and Myth in Malay Healing Arts. PhD Thesis. Michigan, USA - London, England: University Microfilms International.

Dentan, R, K. - 1988 On Reconsidering Violence in Simple Human Societies. In Current Anthropology Vol. 29. No. 4.

Dentan, R, K. - 1968 The Semai - A Nonviolent People of Malaya. London: Holte, Rinehart and Winston.

Geertz, C. - 1973. Religion as a cultural system. In the Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Gianno, R. - 1985 Semelai Resin Technology. PhD Thesis. Michigan, USA - London, England: University Microfilms International.

Greenhouse, C. J. - 1982. Looking at Culture, Looking for Rules. In Man Vol. 17. No 1.

Hallowell, A. I. - 1971. Culture and Experience. New York: Schocken Books.

Hobart, M. - 1979. A Balinese village and its field of social relations. PhD Thesis.

Hobart, M. - 1982. Meaning or Moaning? an ethnographic note on a little understood tribe In Semantic Anthropology. ASA 22, ed. D.J. Parkin. London:Academic Press.

Hutterer, K, L. Rambo, A, T. and Lovelace, G. (eds). - 1985 Cultural Values and Human Ecology in Southeast Asia. Michigan papers on South and Southeast Asia Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies. The University of Michigan. Number 27.

Jennings, S. - 1995 Theatre Ritual and Transformation - The Senoi Temiars. London and New York: Routledge.

Karim, W, J, B. - 1981 Ma' Betisek Concepts of Living Things. New Jersey: The Athlone Press.

Kasimin, A. - 1991 Religion and Social Change among the Indiginous People of the Malay Penisula. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka Kementerian Pendidikan.

La Fontaine, J. - 1988. Child Sexual Abuse and the Incest Taboo: Practical Problems and Theoretical Issues. In Man Vol. 23. No.

Lambek, M. - 1992. Taboo as Cultural Practice Among Malagasy Speakers. In Man Vol. 27. No.2.

Mauss, M. - 1950 The Gift. Reprinted 1993. London: Routledge.

McNay, L. - 1992 Foucault and Feminism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Mead, G. H. - 1934. Mind, Self and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Means, G, P. (ed). - 1986 Sengoi - English, English - Sengoi Dictionary. University of Toronto, York University: The Joint Centre on Modern East Asia.

Midgley, M. - 1978 Beast and Man - The roots of human nature. Bristol: Methuen.

Moore, H. L. - 1994. A Passion for Difference. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Needham, R. - 1981 Inner States as Universals: sceptical reflections on human nature. In Indiginous Psychologies. eds. P. Heelas and A. Locke. London: Academic Press.

Needham, R. - 1976. Skulls and Causality. In Man Vol. 11. No. 1.

Osman, M. T. - 1967. Indiginous Hindu and Islamic Elements in Malay Folk Beliefs. Dissertation: Indiana University.

Overing, J. (ed) - 1985 Reason and Morality. London and New York: Tavistock Publications.

Ouroussoff, A. - 1993. Illusions of Rationality: False Premises of the Liberal Tradition. In Man Vol. 28. No. 2).

Parkin, D. - 1986. Violence and Will. In The Anthropology of Violence. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Parkin, D. (ed) - 1985 The Anthropology of Evil. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Ltd.

Rahula, W. - 1959 What the Buddha Taught. Old Woking, Surrey: Unwin Brothers Ltd.

Robarchek, C, A. - 1986 Helplessness, Fearfulness, and Peacefulness: The Emotional and Motivational Contexts of Semai Social Relations. Michigan: Anthroplogy Quarterly.

Robarchek, C, A. - 1977 Frustration, Aggression, and the Nonviolent Semai. In American Ethnologist Vol. 4. No. 4.

Roseman, M. - 1991 Healing Sounds from the Malaysian Rainforest. Berkely, London: University of California Press.

Roseman, M. - 1987 Six month report of research among the Temiars, Kelantan, Malaysia.

Said, E, W. - 1978 Orientalism - western conceptions of the orient. London: Penguin.

Skeat, W, W. - 1900 Malay Magic. London: Macmillan and Co Ltd. (reprinted 1967 Dover Publications, Inc: New York).

Suzuki, T and Ohtsuka, R. (eds). - 1987 Human Ecology of Health and Survival in Asia and the South Pacific. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Tsing, A, L. - 1993 In the Realm of the Diamond Queen. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Tyler, E. B - 1871. Primitive Culture. London: John Murray.

Wilshire, B. - 1982. Role Playing and Identity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press

The above essay was written by Andy Hickson and is © July 1997 Please send any feedback via e-mail.

Return to home page.